In this dazzling debut, Stegner Fellow Jemimah Wei explores the formation and dissolution of family bonds in a story of ambition and sisterhood in turn-of-the-millennium Singapore.

Sexual assault.

Before Arin, Genevieve Yang was an only child. Living with her parents and grandmother in a single-room flat in working-class Bedok, Genevieve is saddled with an unexpected sibling when Arin appears, the shameful legacy of a grandfather long believed to be dead. As the two girls grow closer, they must navigate the intensity of life in a place where the urgent insistence on achievement demands constant sacrifice. Knowing that failure is not an option, the sisters learn to depend entirely on one another as they spurn outside friendships, leisure, and any semblance of a social life in pursuit of academic perfection and passage to a better future.

When a stinging betrayal violently estranges Genevieve and Arin, Genevieve must weigh the value of ambition versus familial love, home versus the outside world, and allegiance to herself versus allegiance to the people who made her who she is. In the story of a family and its contention with the roiling changes of our rapidly modernizing, winner-take-all world, The Original Daughter is a major literary debut, rife with emotional clarity and searing social insight.

Don't just take our word for it...

“I laughed, I wept, I called my mom. Instantly and utterly enchanting, reading The Original Daughter felt analogous to being a child again, pushing off real life just so I could stay in the warmth of its pages a second longer. This story of a family and its struggle for freedom, intimacy, and survival asks not just what it means to love, but love well, especially in a world where our relationships can both bond and break us. Jemimah Wei chronicles the eviscerating experience of living under the fracture of modern society with devastating care. Seismic.”

– Jonathan Escoffery, Booker Prize nominee and bestselling author of If I Survive You

“Fiery, funny, and incisive, The Original Daughter is at its core a ghost story. Once, invisibility was the hallmark of the working class, but Jemimah Wei knows in today’s world, where an internet connection allows one to walk through walls, be seen, disappear, and haunt from beyond the analog grave, a soulless transparency is power. A societal privilege ironically afforded to most everyone. This novel adroitly, yet playfully, turns the ways we see cultural appropriation, nepotism, and identity upside down. What a wise and wonderful read.”

– Paul Beatty, author of The Sellout

“Jemimah Wei’s debut The Original Daughter goes for all the big stuff: ambition, time, family, forgiveness, constructing the self. Thrilling, to find a new author with an appetite for the whole spectrum of living, and the skill to get it down true. A contract of sisterhood is signed, then life, then ambition, then disappointment and heartbreak and and and. Wei’s prose is delicious, propulsively hurdling us through the lives of Gen and Arin, who will live in my marrow forever. The Original Daughter is so much the real deal.”

– Kaveh Akbar, bestselling author of the National Book Award nominee Martyr!

Taste the very first page

Arin was somewhere in Germany when my mother got sick again. She’d been sick before, but never like this, and I knew it was only a matter of time before she would change her mind and start asking for Arin. The prospect filled me with dread. My sister and I hadn’t spoken for years, not since she first got famous, not even when my mother was diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer a couple of years ago. Back then, too, I’d been afraid that if things got really bad, my mother would want Arin there. But we’d had her breasts lopped off, one after the other, and it appeared to have stopped the cancer’s spread. The subject of Arin never came up.

Our relationship hadn’t been good for a long time, and in recent years my mother’s irreverence had dampened into a more respectable muteness. But after she recovered, my mother immediately became irritating again. She’d lost so much weight from the chemotherapy, it didn’t seem to matter that she had no breasts. She sheared off her fluffy black hair, wore nothing but singlets and shorts, and gleefully told everyone passing by the photocopy shop that between this and menopause, she was finally relieved of the trappings of being a woman. The word she used, one I caught her selecting carefully from the Oxford English Dictionary by our sole electric night-light, was “liberation.”

Liberation? When had she ever not acted exactly as she pleased? I felt that she was baiting me; I refused to respond. Then, a few days ago, I woke to find my mother still in bed beside me, one arm thrown over her face.

“Ma,” I said. “It’s eight.”

She was usually out of the house by six, either at the wet market or doing exercises at Bedok Reservoir Park with her tai chi group before opening the photocopy shop. To her, sleeping in was something only rich people did, a sign of weak character.

You might also like

RomanceDebut NovelIncludes a Dog

Any Trope But You

A bestselling romance author flees to Alaska to reinvent herself and write her first murder mystery, but the rugged resort proprietor soon has her fearing she’s living in a rom-com plot instead.

ThrillerContemporaryDebut Novel

Tilt

Annie is nine months pregnant. She’s shopping for a crib at IKEA. That’s when the massive earthquake hits. There’s nothing to do but walk.

Historical FictionDebut NovelMagical Realism

Junie

A young girl must face a life-altering decision after awakening her sister’s ghost, navigating truths about love, friendship, and power as the Civil War looms.

Good Girl

An electric debut novel about the daughter of Afghan refugees and her year of self-discovery and a portrait of the artist as a young woman set in a Berlin that can’t escape its history.

Dead Money

Featuring jaw-dropping twists and a wily, outsider heroine you can’t help rooting for, Dead Money is a brilliant sleight-of-hand mystery.

After the Ocean

A painful unsolved mystery resurfaces after decades of confusion, sending one woman and her daughters on a journey of redemption in this emotional story about intergenerational trauma, family, and the beauty of Puerto Rico.

Unromance

A recently dumped TV heartthrob enlists a jaded romance novelist to ruin romance for him—one rom-com trope at a time—so he never gets swept off his feet again…

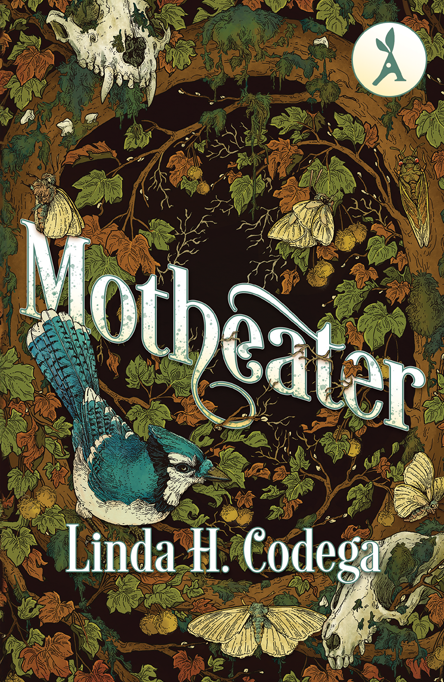

Motheater

In this nuanced queer fantasy set amid the Appalachian Mountains in Virginia, the last witch of the Ridge must choose sides in a clash between industry and nature.

Historical FictionDebut NovelLGBTQIA+Gothic FictionDark Academia

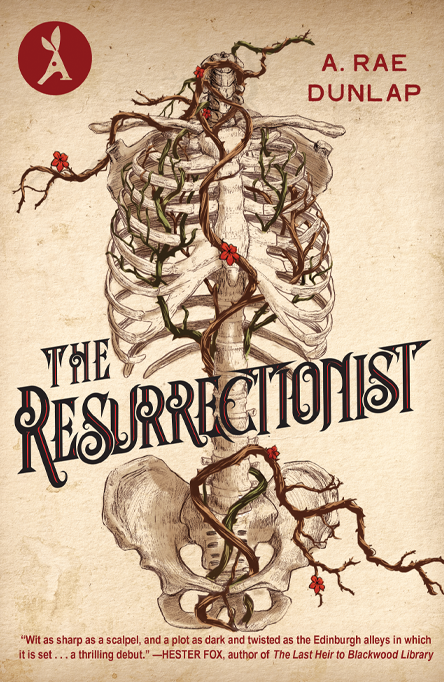

The Resurrectionist

A twisty gothic debut set when real-life serial killers Burke and Hare terrorized the streets of Edinburgh, as a young medical student is lured into the illicit underworld of body snatching.

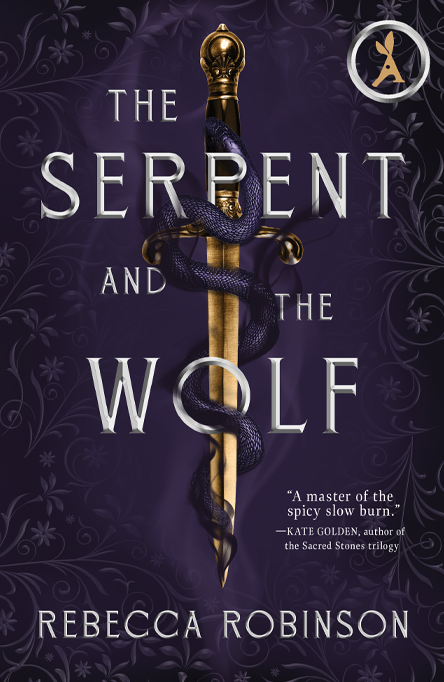

The Serpent and the Wolf

A thrilling romantasy debut combines high-stakes political intrigue and a steamy, slow-burn, enemies-to-lovers romance.

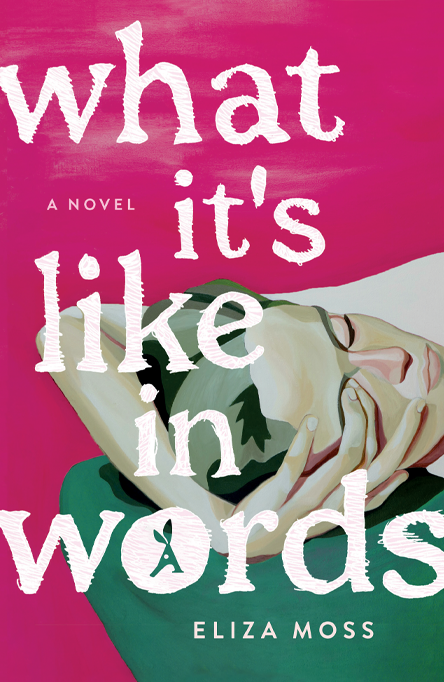

What It’s Like in Words

A dark, intense, and compelling account of what happens when a young woman falls in love with the wrong kind of man.

Like Mother, Like Mother

An enthralling novel about three generations of strong-willed women, unknowingly shaped by the secrets buried in their family’s past.

Historical FictionDebut NovelIncludes a Dog

Eleanore of Avignon

The story of a healer who risks her life, her freedom, and everything she holds dear to protect her beloved city from the encroaching Black Death.

Colored Television

A brilliant dark comedy about love and ambition, failure and reinvention, and the racial-identity-industrial complex.

The Truth According to Ember

A Chickasaw woman who can’t catch a break serves up a little white lie that snowballs into much more in this witty and irresistible rom-com by debut author Danica Nava.

Mistress of Lies

A villainous, bloodthirsty heroine finds herself plunged into the dangerous world of power, politics and murder in the court of the vampire king in this dark romantic fantasy debut.

Catalina

by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

A year in the life of the unforgettable Catalina Ituralde, a wickedly wry and heartbreakingly vulnerable student at an elite college.

Historical FictionDebut NovelMagical Realism

Masquerade

Set in a wonderfully reimagined 15th century West Africa, Masquerade is a dazzling, lyrical tale exploring the true cost of one woman’s fight for freedom and self-discovery, and the lengths she’ll go to secure her future.

Whoever You Are, Honey

This darkly brilliant debut novel explores how women shape themselves beneath the gaze of love, friendship, and the algorithm—by a thrilling feminist voice for the age of AI.

ThrillerDebut NovelIncludes a Dog

You Know What You Did

In this heart-pounding debut thriller for fans of Lisa Jewell and Celeste Ng, a first-generation Vietnamese American artist must confront nightmares past and present...

Lovers and Liars

Three wildly different sisters reunite for a destination wedding at an English castle in this heartfelt and rollicking novel from the New York Times bestselling author of The Jetsetters.