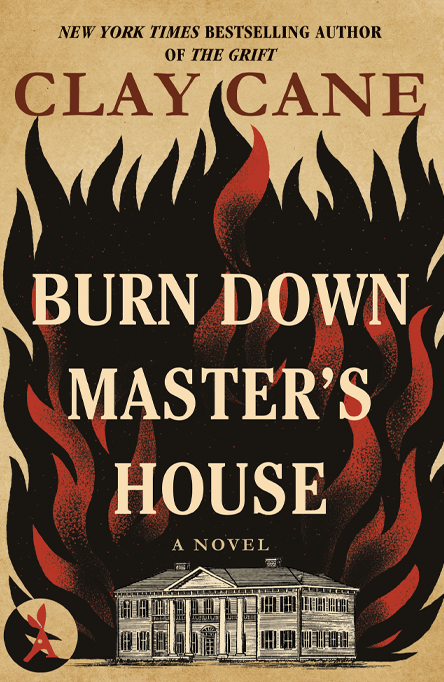

Inspired by true, long-buried stories of enslaved people who dared to fight back, a searing portrayal of resistance for readers of Colson Whitehead, Jesmyn Ward, and Percival Everett, from Clay Cane, award-winning journalist and New York Times bestselling author of The Grift.

Slavery, torture, child abuse, sexual abuse, hate speech.

As turmoil simmers within a divided nation, smoke from another blaze begins to rise. Sparked by individual acts of resistance among those enslaved across the American South, their seemingly disparate rebellions fuel a singular inferno of justice, connecting them in ways quiet at times, explosive at others. As these flames rise, so will they.

Luke, quick-witted and literate, and Henri, a man with a strong and defiant spirit, forge an unbreakable bond at a Virginia plantation called Magnolia Row. Both seek escape from unimaginable cruelty. And sure as the fires of hell, Luke and Henri will leave their mark, sparking resistance among the lives they touch…

One is Josephine, a young, sharp, and observant girl who wields silence as her greatest weapon. A witness to Luke and Henri’s resilience, she listens, watches, waits for the moment to make her move.

Then there is Charity Butler, her husband a formerly enslaved man who proved his ferocity as a young boy standing alongside Josephine. At his encouragement, Charity fights for her freedom in court and wins – only to battle a deeply unjust system designed to destroy the life they’ve built.

And finally, there is Nathaniel, who ruthlessly exploits other Black people and mirrors the cruelty of the white men who, like him, are enslavers. A perversion of the system of slavery, his fragile and contradictory rule will become a catalyst of its own.

Inspired by the true stories of the profoundly courageous men and women who dared to fight back, Burn Down Master’s House is a singular tour de force of a novel—breathtaking in scope, compassion, and a timeliness that speaks powerfully to our present era.

Don't just take our word for it...

“With shades of Kindred, James, and The Prophets, this story belongs to a long tradition of resistance that traces back to 1526, when enslaved Africans burned down their captors’ settlement in what is now South Carolina. Cane — a naturally gifted storyteller — weaves a brutal, bold narrative.”

– Keith Boykin, New York Times bestselling author of Why Does Everything Have to Be About Race?

“To refill my well of radical hope, I read resistance stories. Whether from history or from historical imagination. Burn Down Master’s House is a resistance story for the ages. Clay Cane’s gripping novel is based on real stories of enslaved women and men, of their audacious struggle against slavery.”

– Ibram X. Kendi, National Book Award-winning author of Stamped from the Beginning

“A bold and unflinching novel, Burn Down Master’s House reclaims the lost voices of American slavery and fearlessly confronts myths that whitewash history. A powerful fiction debut that demands to be read.”

– Angie Thomas, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Hate U Give

Taste the very first page

The cabin was beaten down by humiliation and despair, infesting every corner of the caged space. The filth was stitched into the walls, into the hay-strewn dirt floor, into the rusted hinges of the door that never closed all the way. The cramped room was a sweatbox and a stage all at once. “Please, Henri, just do it,” Suzie begged. She sat hunched on the floor, clutching the remains of a blanket to her bare chest. Her eyes pleading with him more than her words ever could.

Henri’s body betrayed him, as it always had in moments like this. He hated himself for the way he went limp, the way the thought of touching Suzie—of giving the master what he wanted—felt like a death he couldn’t bear.

Suzie sighed with unsympathetic frustration. “Why can’t you just give me some babies, like Master said? You know what’ll happen if you don’t.”

Henri stared at her. Suzie was the oldest girl on the plantation who hadn’t birthed any property, and he was the lone man who hadn’t fathered any field hands. They were nothing more: failed machines in an apparatus that demanded they work, produce, and abide. Suzie blamed the “African” in his blood for what she saw as stubbornness. Henri sat back, his hands resting on his knees, his broad shoulders slumping. “Think I don’t know?” he said. “Think I don’t know what happens when they don’t get what they want? But it ain’t just about babies, Suzie. We not making no children here. We making slaves.”

You might also like

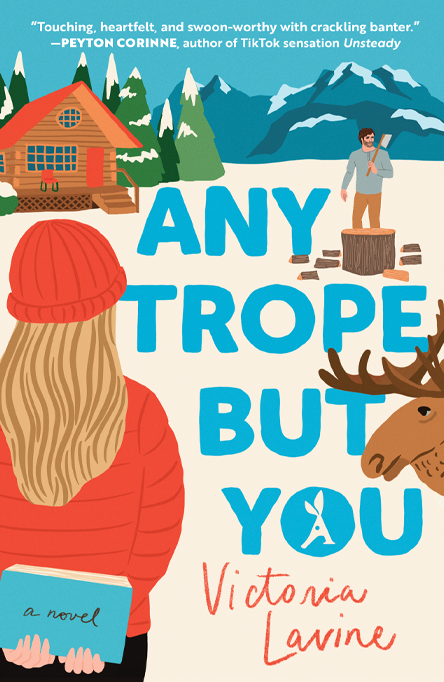

RomanceDebut NovelIncludes a Dog

Any Trope But You

A bestselling romance author flees to Alaska to reinvent herself and write her first murder mystery, but the rugged resort proprietor soon has her fearing she’s living in a rom-com plot instead.

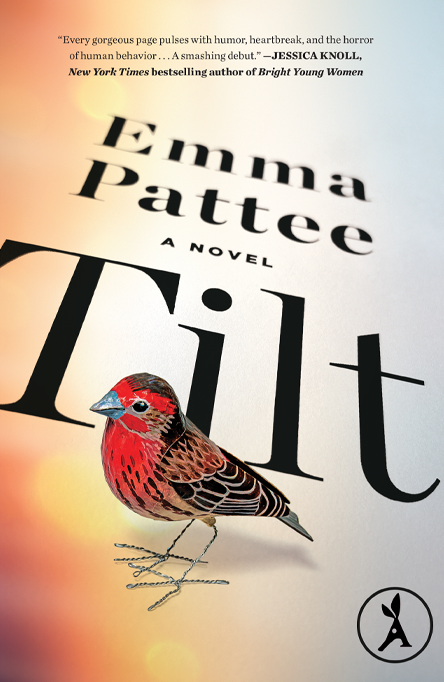

ThrillerContemporaryDebut Novel

Tilt

Annie is nine months pregnant. She’s shopping for a crib at IKEA. That’s when the massive earthquake hits. There’s nothing to do but walk.

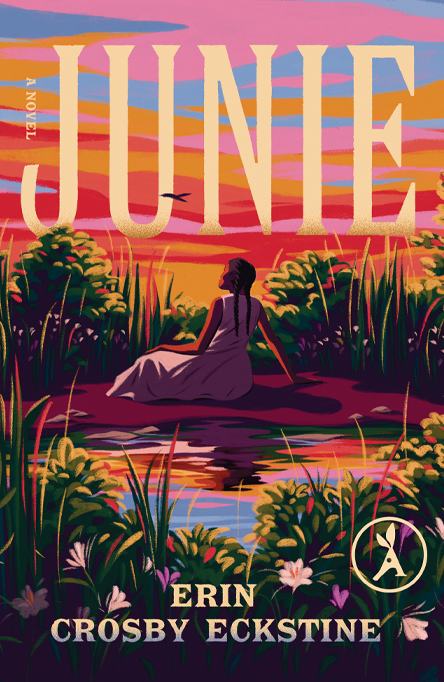

HistoricalDebut NovelMagical Realism

Junie

A young girl must face a life-altering decision after awakening her sister’s ghost, navigating truths about love, friendship, and power as the Civil War looms.

Good Girl

An electric debut novel about the daughter of Afghan refugees and her year of self-discovery and a portrait of the artist as a young woman set in a Berlin that can’t escape its history.

Dead Money

Featuring jaw-dropping twists and a wily, outsider heroine you can’t help rooting for, Dead Money is a brilliant sleight-of-hand mystery.

The Reformatory (2024 Members’ Choice)

A gripping, page-turning novel set in Jim Crow Florida that follows Robert Stephens Jr. as he’s sent to a segregated reform school that is a chamber of terrors where he sees the horrors of racism and injustice, for the living, and the dead.

Unromance

A recently dumped TV heartthrob enlists a jaded romance novelist to ruin romance for him—one rom-com trope at a time—so he never gets swept off his feet again…

Motheater

In this nuanced queer fantasy set amid the Appalachian Mountains in Virginia, the last witch of the Ridge must choose sides in a clash between industry and nature.

HistoricalDebut NovelLGBTQIA+Gothic FictionDark Academia

The Resurrectionist

A twisty gothic debut set when real-life serial killers Burke and Hare terrorized the streets of Edinburgh, as a young medical student is lured into the illicit underworld of body snatching.

The Serpent and the Wolf

A thrilling romantasy debut combines high-stakes political intrigue and a steamy, slow-burn, enemies-to-lovers romance.

What It’s Like in Words

A dark, intense, and compelling account of what happens when a young woman falls in love with the wrong kind of man.

HistoricalDebut NovelIncludes a Dog

Eleanore of Avignon

The story of a healer who risks her life, her freedom, and everything she holds dear to protect her beloved city from the encroaching Black Death.

The Truth According to Ember

A Chickasaw woman who can’t catch a break serves up a little white lie that snowballs into much more in this witty and irresistible rom-com by debut author Danica Nava.

Mistress of Lies

A villainous, bloodthirsty heroine finds herself plunged into the dangerous world of power, politics and murder in the court of the vampire king in this dark romantic fantasy debut.

Catalina

by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

A year in the life of the unforgettable Catalina Ituralde, a wickedly wry and heartbreakingly vulnerable student at an elite college.

HistoricalDebut NovelMagical Realism

Masquerade

Set in a wonderfully reimagined 15th century West Africa, Masquerade is a dazzling, lyrical tale exploring the true cost of one woman’s fight for freedom and self-discovery, and the lengths she’ll go to secure her future.

Whoever You Are, Honey

This darkly brilliant debut novel explores how women shape themselves beneath the gaze of love, friendship, and the algorithm—by a thrilling feminist voice for the age of AI.

ThrillerDebut NovelIncludes a Dog

You Know What You Did

In this heart-pounding debut thriller for fans of Lisa Jewell and Celeste Ng, a first-generation Vietnamese American artist must confront nightmares past and present...